The Confession of The Presbyterian Church in Canada

This web-exhibit contains content that may be triggering for some researchers. If you are a Residential School Survivor in need of support, please contact the 24-Hour National Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419.

Residential Schools and Mission Work

The Presbyterian Church in Canada began education focused mission work with Indigenous peoples in the mid-1860s. The Church established day schools on a number of reserves. In day schools, children would attend school during the day and go home at night. By the 1880s, however, the Federal Government preferred developing off-reserve Residential Schools as opposed to continuing the development of day schools. This meant that children would need to leave their communities and travel, in some cases, hundreds of kilometers to attend school. Children would only be able to return home for Christmas and summer holidays. A third type of school that was developed was industrial schools, which were residential vocational training schools for adolescents. The Presbyterian Church partnered with the government to establish and operate these new schools. The Foreign Missions Committee of The Presbyterian Church in Canada and the Woman’s Missionary Society assumed responsibility for the operation of the Residential Schools while the government provided funding and oversight. These schools were inspected by the Federal Government’s Department of Indian Affairs. By 1920, under the Indian Act, it became mandatory for every Indigenous child to attend Residential School.

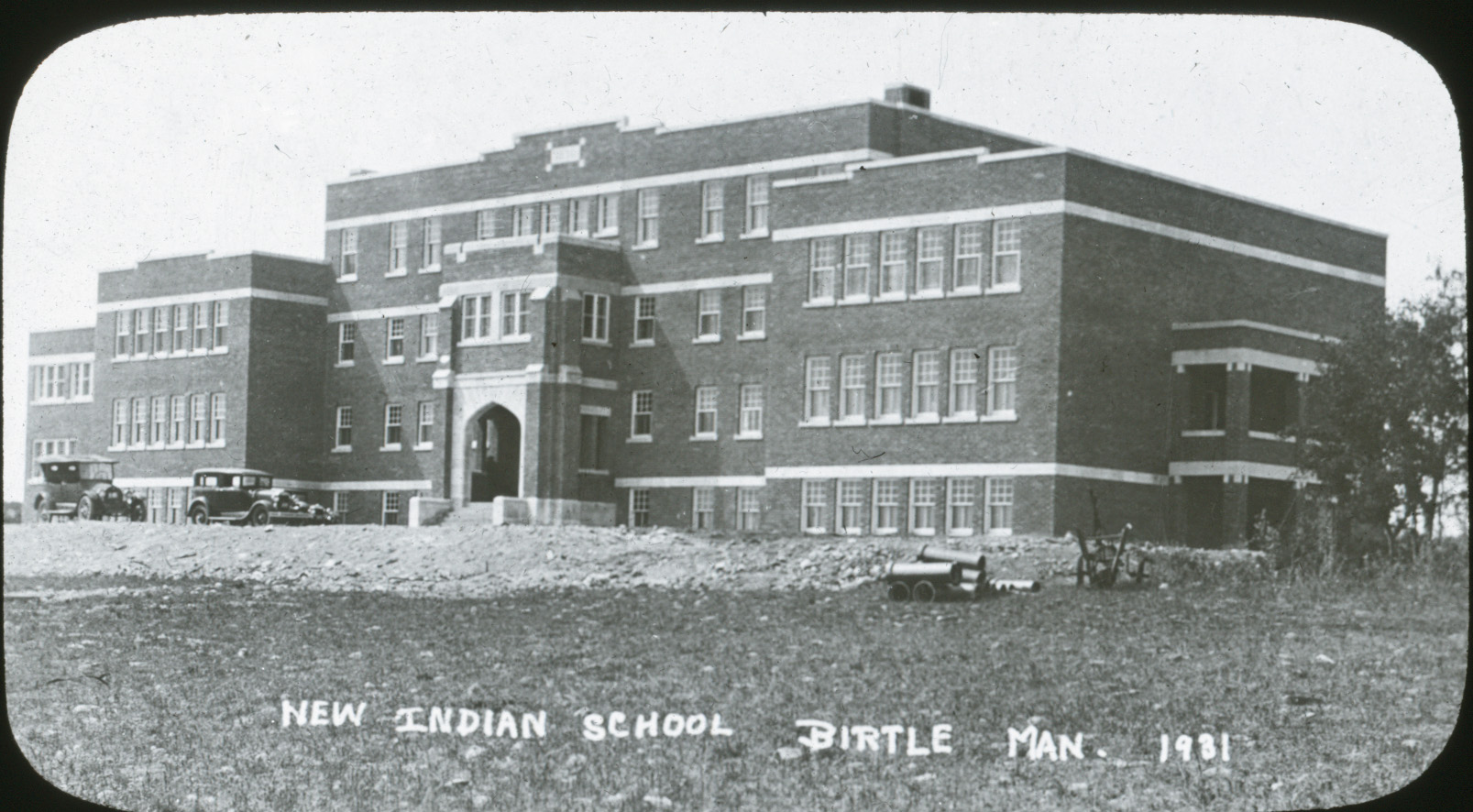

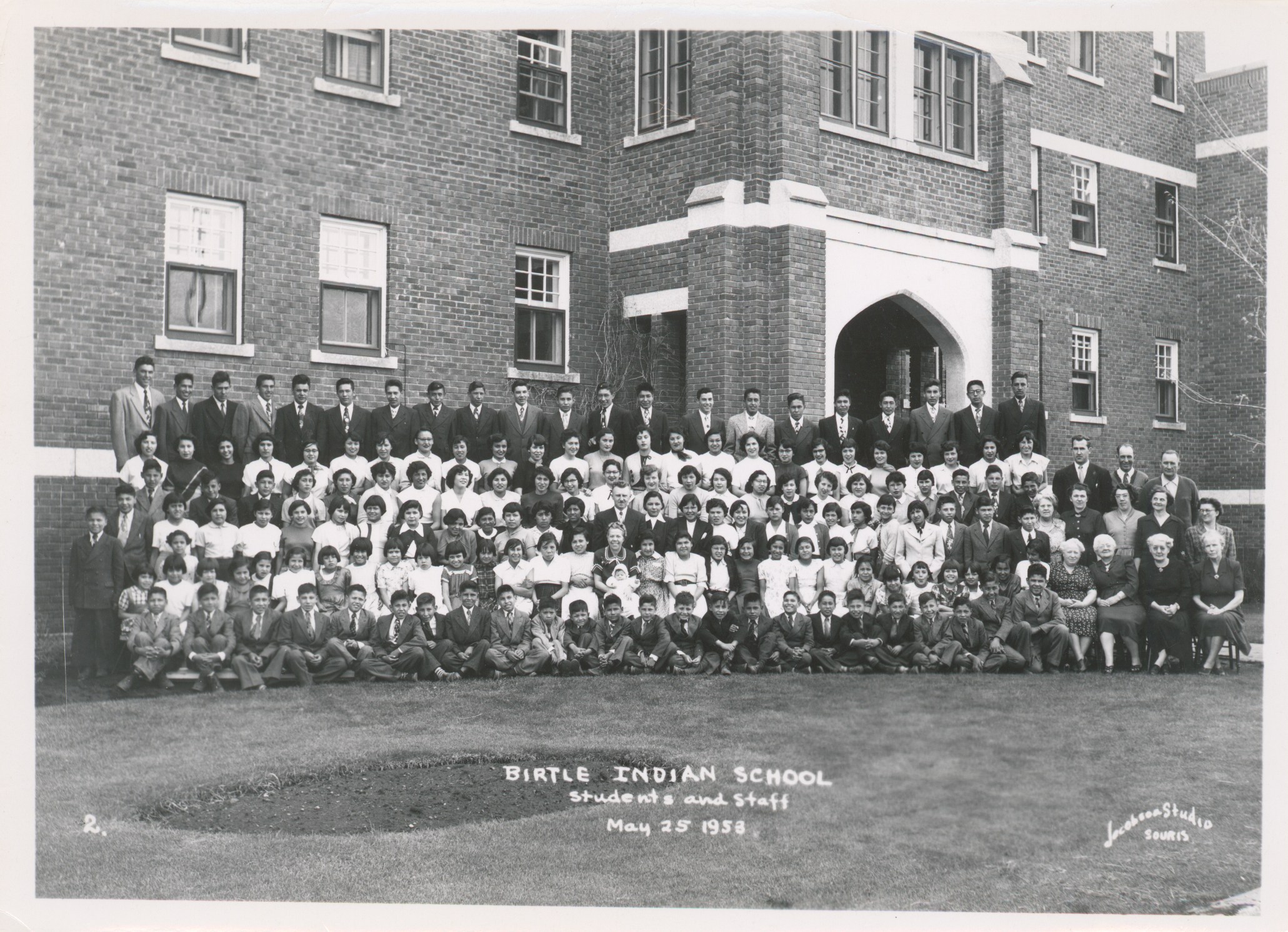

The Presbyterian Church in Canada operated eleven Residential Schools for Indigenous peoples from the mid-1880s until 1969. These schools were: Ahousaht Residential School in British Columbia, Alberni Residential School in British Columbia, Birtle Residential School in Manitoba, Cecilia Jeffrey Residential School, first located in Shoal Lake, Ontario and relocated to Kenora, Ontario, Crowstand Residential School in Saskatchewan, File Hills Residential School in Saskatchewan, Muscowpetung (later known as “Lakesend”) Residential School in Saskatchewan, Portage la Prairie Residential School in Manitoba, Regina Industrial School in Saskatchewan, Round Lake Residential School in Saskatchewan, and Stoney Plain Residential School in Alberta . In 1925, operation for majority of these schools was transferred to The United Church of Canada, which was established as the result of the Church Union Movement. This left The Presbyterian Church with two schools: Birtle School and Cecilia Jeffrey School. By 1969, the Residential School system became the full responsibility of the Canadian Federal Government.

The Boarding School…tries to teach them [Indigenous children] new conditions of living…to eat different food, to sleep in beds, to dress, wash, bath, to bake their bread, to cook their food, keep their houses and make a living on farms etc., – not like their parents have done but in a manner that shall enable them to live in civilized conditions.

– Rev. F.E. Pitts, principal of Birtle School, 1923 (Bush, 2004, p. 3)

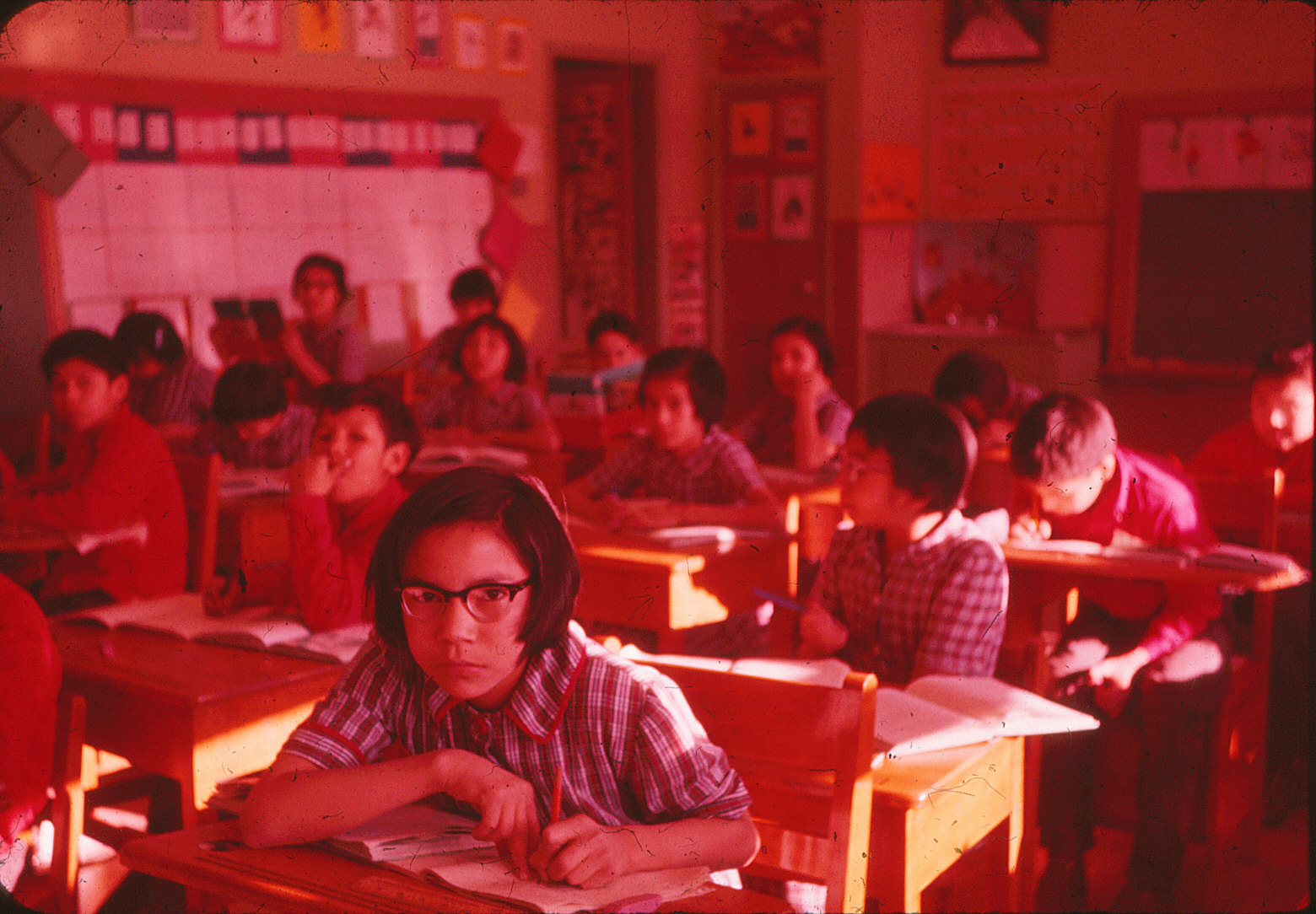

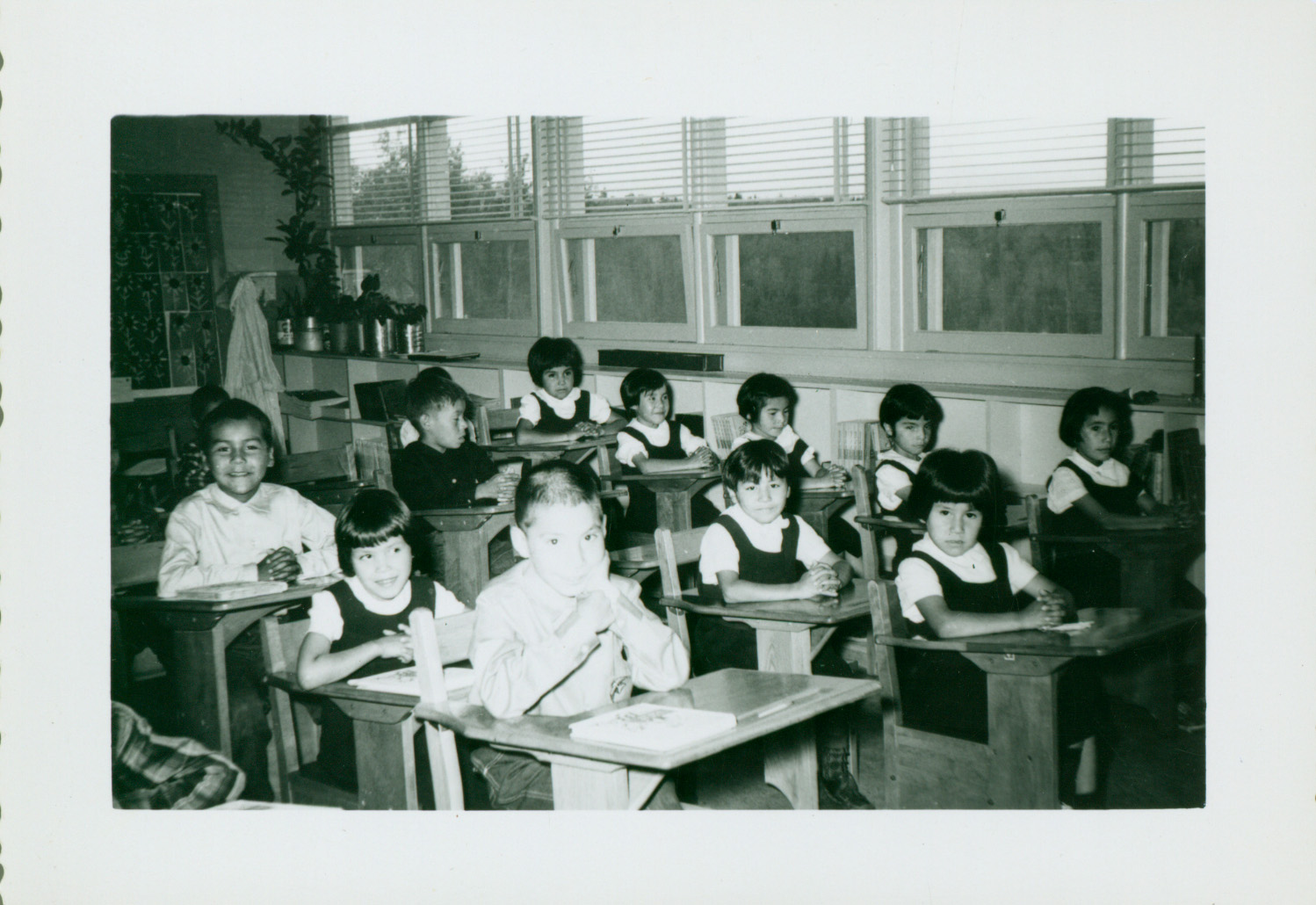

As part of the Residential School system, Indigenous children were removed and isolated from the influence of their communities. Students were forbidden to speak their own languages or take part in Indigenous practices. Students were punished for doing so. Indigenous children were forced to speak English, learn manual labour and domestic work such as farming and sewing, and were instructed in Euro-Canadian household customs. By depriving Indigenous children of their traditional culture, Residential Schools served to assimilate students into the dominant Euro-Canadian culture. Residential Schools also allowed the Presbyterian Church to carry out its missionary goals, as it was believed that newly converted students would return home as Christian missionaries to their communities.

There were many issues with the Residential School system. The Federal Government failed to provide adequate funding for the schools to function effectively. This resulted in poor quality of education, as schools were forced to implement a half-day system. Indigenous children would attend class for half a day, with the other half of the day spent helping to sustain their school. Students were tasked with various activities to reduce school costs such as gardening to provide food for the schools and cutting wood to heat the schools. Consequently, the half-day system meant that students most often took two years to pass one grade level. By the time students reached 16 years old, many of them were taking the grade 5 curriculum. Inadequate funding also meant that Residential Schools were often overcrowded with poor sanitation and health care. It was common for Residential Schools to have high mortality rates. In an environment where teachers and staff had total control, Residential Schools often exposed Indigenous children to racist and dehumanizing disciplinary practices. Many children were verbally, physically, sexually and psychologically abused. This includes children who attended schools operated by The Presbyterian Church in Canada. The Residential School system created devastating long term effects on Indigenous communities across Canada. This includes high rates of suicide, drug and alcohol abuse, and loss of Indigenous languages and traditions.

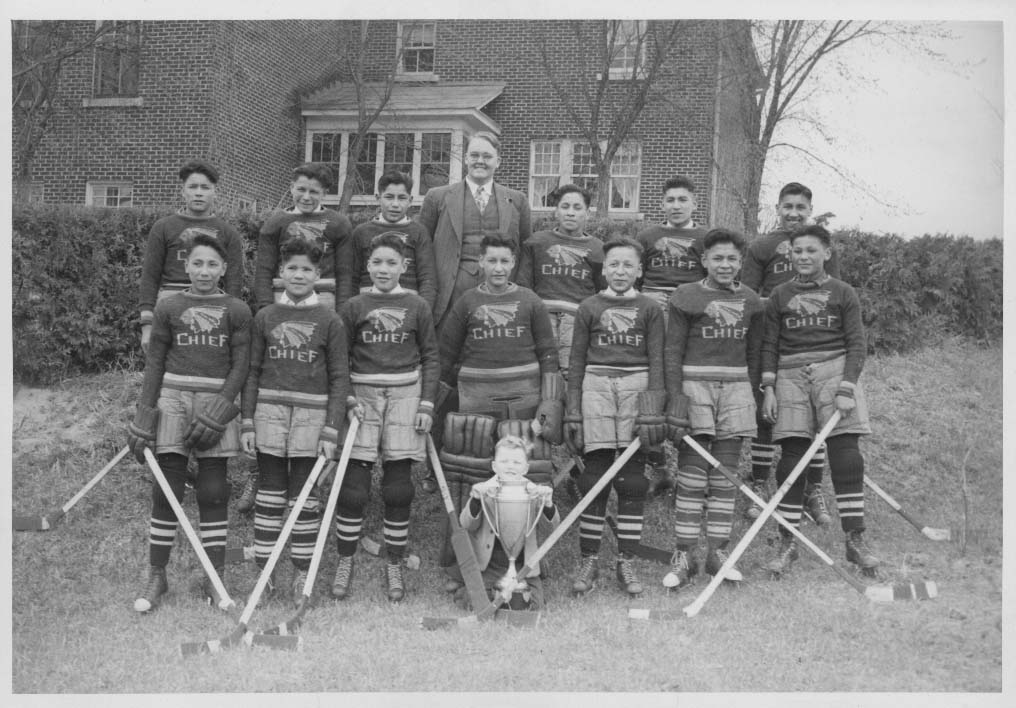

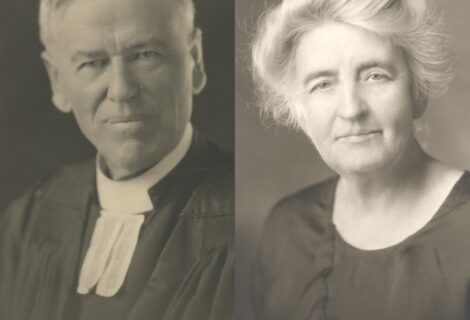

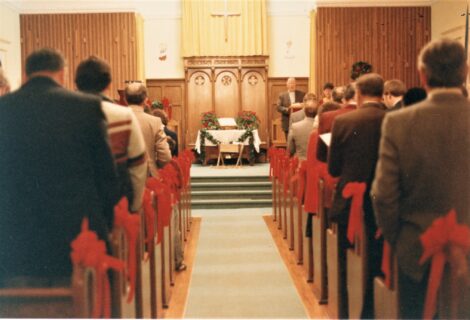

Photographs from Birtle and Cecilia Jeffrey Residential Schools

This Project has been made possible [in part] by the Government of Canada through the Young Canada Works and Heritage Organizations Program. « Ce projet a été rendu possible [en partie] grâce au gouvernement du Canada par de Jeunesse Canada au travail et le Programme des organismes patrimoniaux». This exhibit was created by the Archives summer intern, Melissa Nelson.

*Copyright 2012 – The Presbyterian Church in Canada

If you wish to quote or use any part of this website exhibit, please give credit to The Presbyterian Church in Canada Archives.