Cecilia Jeffrey School

This web-exhibit contains content that may be triggering for some researchers. If you are a Residential School Survivor in need of support, please contact the 24-Hour National Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419.

The first Cecilia Jeffrey Boarding/Residential School was built in 1901 near Shoal Lake (Lake of the Woods), Ontario. The buildings were located in a beautiful but remote part of Shoal Lake, and housed the school’s first cohort of students in 1902. For staff, the process of getting to the school was arduous.

[O]ne of our most isolated institutions, the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian School, on Shoal Lake, a beautiful spot, yet completely cut off, with neither telephone nor telegraph. Even His Majesty’s mail is only possible when our little boat can cross the eight miles of water to the spur line of railway which carries passengers twice a week…. The school is full to capacity with about 70 children, and many are still roaming the reserves unschooled. Before long the Government hopes to build us a second school in a more accessible location (MacGillivray, March 1923, p.75-76).Cecilia Jeffrey School, which is situated in the heart of some of the most beautiful lake scenery in Canada…. To describe the five hour trip from Kenora to the school on board the Wanderer one would need the gift of our best writers, and even then would fall short in conveying to others an adequate conception of the beauty of the lake with its 6,000 islands (Donaghy, October 1915, p.279-281).

The school itself was founded under unusual processes.“The three First Nations that would be sending children to the school and the Presbyterian Church entered into an agreement about how the school was to be operated” (Bush, 2017, p. 37). This type of agreement was very unusual, and was further unique in that the Ojibwa band of Shoal Lake had “petitioned the Presbyterians to set up a school for their children, and two years later, the missionary on the spot reported that they were ‘not only willing but anxious for a boarding school’” (Miller, 1996, p. 118-120). Miller explains:

The document [contractual agreement] limited proselytization and the amount of work children could be required to perform, guaranteed that pupils could be removed one at a time to participate in traditional Ojibwa rituals, and promised that the police would not be used to force runaway children to return to the school. The first clause, for example, stipulated ‘that while children are young and at school they shall not be baptized without the consent of their parents,’ and the sixth ensured that ‘little children (under 8 years) shall not be given heavy work and larger children shall attend school, at least half of each school day.’ Perhaps the most revealing article was the one that said that ‘a number of children shall be sent now and if they are well treated more shall be sent’” (Miller, 1996, p.118-120).

Despite the stipulations of this contact, students at Cecilia Jeffrey Residential School were subject to the abuse, poor quality of life, and “cultural genocide”, typically associated with the Canadian Residential Schooling system. Cultural genocide, or “the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group” (TRC Summary, 2015, p.1), is a term commonly associated with the treatment of Indigenous peoples by settler-Canadians.

States that engage in cultural genocide set out to destroy the political and social institutions of the targeted group. Land is seized, and populations are forcibly transferred and their movements restricted. Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. And, most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next. In its dealing with Aboriginal people, Canada did all these things (TRC Summary, 2015, p.1).

In understanding the intricacies of cultural genocide, the Residential Schooling system becomes a key component of the destruction of Indigenous culture. The students of Cecilia Jeffrey School experienced this in a myriad of ways: they were removed from their families, communities, and cultural leaders and were expected to assimilate to settler-Canadian culture. In addition to this, the students at Residential Schools also faced illness, experimentation, abuse, and premature death.

Although poor living conditions, overcrowding, and negligence are the failures most associated with Cecilia Jeffrey school, a number of reports also speak to the physical, sexual, and emotional abuse suffered by students. The TRC Summary, Miller, and Milloy attest that:

Policies that were seen as being unacceptable in the early twentieth century were still in place in the 1960s. Many students compared Residential Schools to jails: some spoke of being locked in in their dormitories, broom closets, basements, and even crawl spaces. In 1965, students who ran away from the Presbyterian school in Kenora were locked up with just a mattress on the floor and put on a bread-and-milk-diet (TRC Summary, 2015, p. 104).

At the “Presbyterian school in northwestern Ontario in 1910-1911” [Cecilia Jeffrey], “a number of the girls informed the assistant matron that the principal had had girls ‘put their hands under his clothing and [play] with his breasts’, and that ‘he was in the habit of kissing the older girls’” (Miller, 1996, p. 330).

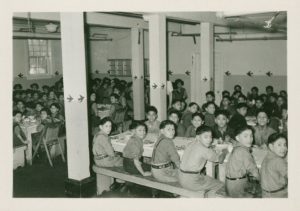

Two girls had been “humiliated by being made to come down to eat in the dining hall dressed only in their underwear”. The Principal, S.T. Robinson, on being questioned, admitted according to the article, that he had employed such disciplinary measure in his battle against runaways (Milloy, 1999, p.288-289).

Beyond the behavior exhibited by the staff at the school, the living conditions at Cecilia Jeffrey were not conducive to health and happiness for students. After witnessing the rampant spread of disease and injury at the school, nurse Kathleen Stewart wrote: “it is more like a convalescent home for children than a school” (Bush, 2014, p. 2). As a statement on the inadequate health and safety of children at Cecilia Jeffrey, Bush writes:

[E]leven students [in 1954] had had tonsillectomies, and one student had been fitted with an artificial leg due to an accident. All of this was in addition to the regular bumps, bruises, scrapes, and flu symptoms that were part of having 165 students living in the school. Stewart estimated in the first three months of 1954 she handled 2,733 visits from or to students and staff. In addition to the children who were treated at the school, in 1954, students were sent to a sanatorium for treatment of tuberculosis (Bush, 2014, p. 2-3).

Although Kathleen Stewart served as a nurse to the students and staff of Cecilia Jeffrey school in the 1950s, the presence of medical professionals was not always guaranteed and their practice was not always effective or ethical. In treating ear problems in students, nurse Kathleen Stewart has been criticized by contemporary researchers and social justice advocates for using experimental ear cleaning methods on non-consenting students. Ear cleaning remedies were administered in conjunction with other medical tests, including regularly drawing student blood to monitor hemoglobin levels (Bush, 2014, p. 2).

Lack of adequate funding and nutrition compounded the health difficulties faced by students. The Canadian federal government along with the Women’s Missionary Society (WMS) of The Presbyterian Church in Canada were the entities responsible for funding the Residential School mission work. While the WMS attempted to keep their donations equal over time, the funds from the Government of Canada fluctuated each year. Times of economic downturn took a particular toll on Residential School funding at both the Government and Church levels.

When funding was cut during the Depression of the 1930s, it was the students who paid the price – in more ways than one. At the end of the 1930s, it was discovered that the cook at the Presbyterian school at Kenora was actually selling bread to students, at a rate of ten cents a loaf. When asked if the children got enough to eat at meals, she responded, ‘Yes, but they were always hungry.’ The Indian agent ordered an end to the practice. The fact that hungry students would be reduced to buying bread to supplement their meals in 1939 highlights the government’s failure to provide schools with the resources needed to feed students adequately” (TRC Summary, 2015, p.87).

The cuts in grants that came in 1914 and again during the Depression and the Second World War made the task of feeding the children even more difficult. J.T. Ross, the Principal of Cecilia Jeffrey School, Kenora, informed the Department that despite the across-the-board $10 increase in 1917, the ‘per capita grant is not sufficient to meet our needs in buying food for the children.’ It is ‘absurd to imagine that an Indian child can be properly fed on 40 cents per day leaving clothing out of the question (Milloy, 1999, p.118).

The impact of the First and Second World Wars on students in the Residential School system was not exclusively financial, as war-time also provided older students with an opportunity to enlist. During the First World War, some students from Cecilia Jeffrey school elected to leave the Residential School in favour of joining the war effort. In honour of their service, an “Honor Roll” was put on display in 1918:

At Cecilia Jeffrey, “[t]he closing of the school classes took place while your Secretary was here, and the teacher, Miss Brooker, deserves credit…. A unique feature was the unveiling of the Honor Roll of some 15 or 20 boys who had gone to the front” (Missionary Messenger, December 1918, p. 344).

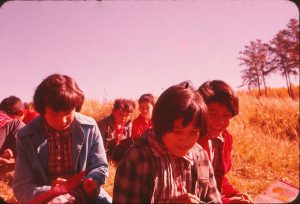

Ultimately, with small budgets and limited resources, the staff at Cecilia Jeffrey Residential School cut costs and made frugal spending decisions. Often, these cuts came at the expense of student wellness. In 2013, it was uncovered that the students at Cecilia Jeffrey were subject to nutritional experiments without their consent, or that of their families, in response to the school’s financial instability. Though illegal in Canada at the time, students were given Newfoundland Flour Mix, “which contained added thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, and bonemeal” (Bush, 2014, p.1).

Cecilia Jeffrey school operated under a half-day system, that both generated funding for the school and was thought to contribute to the education of students. The half-day system mandated that students spend half of their school day in classes, and the other half in vocational training. This meant that boys were expected to train on the school’s farms and gardens, and girls were expected to learn housekeeping and help run the school’s sewing, cooking, and cleaning. In practice, reports testify that vocational training took up a disproportionate amount of student time, and served to both fund the Residential School project and further assimilate Indigenous children into settler-Canadian culture. In his article, Bush asks of Cecilia Jeffrey:

Did the school have enough financial resources to properly feed the students in a way that reflected the culture and practice [of] the student’s home communities? The short answer to that question is “No.” [Cecilia Jeffrey] along with most Indian Residential Schools had their students working large gardens or farms, not for education purposes, but to grow food to supplement the inadequate food budgets (Bush, 2014, p. 2-3).

The lack of financial resources experienced at Cecilia Jeffrey school created a climate in which the abuse of students could occur, and existing prejudices towards Indigenous Peoples and culture exacerbated this behavior within an already failing education system. The cultural assimilation of students, as well as racist and patriarchal attitudes towards Indigenous culture, manifested in both words and action at Cecilia Jeffrey School. Upon arrival at the school, students were often required to cut their hair and give over personal or culturally significant possessions. One student attests that:

On her arrival at the Presbyterian school in Kenora, Ontario, Lorna Morgan was wearing “these nice little beaded moccasins that my grandma had made me to wear to school, and I was very proud of them.” She said they were taken away from her and thrown in the garbage (TRC Summary, 2015, p. 49).

The confiscation of cultural property and removal from cultural practice was not isolated to the beginning of a student’s time at Cecilia Jeffrey School. Instead, the rejection of Indigenous culture, heritage, beliefs, and identity were a pillar of the Residential School curriculum. In a separate portion of the nutritional experimentation undertaken by staff at Cecilia Jeffrey, students were taught about the importance of encouraging the use of settler nutrition practices in their home communities. These foreign nutrition management practices contributed to the further alienation of students from their parents by encouraging the consumption of food that was both too scarce and too expensive to be served in the communities around Cecilia Jeffrey. Bush writes: “what was a parent to do? How would a child view their parent, if the parent was unable to provide what the nutrition team said was an appropriate diet? Further, how much of determining if a diet is appropriate is in fact an evaluation of culture?” (Bush, 2014, p. 2).

For many within the Church, helping those in need was the basis for providing schooling to Indigenous children. Underpinning this desire to help, however, were the latent racist attitudes and assumptions of superiority held by most settler-Canadians towards Indigenous people and culture. Terms such as “heathen”, “pagan”, and “uncivilized” were often used by the Women’s Missionary Society and the wider Church in describing Indigenous people. Sadly, these assumptions of superiority were then used as justification not simply to provide education but to impose settler-Canadian culture on Indigenous Peoples without their input, wishes, or consent.

No report of the committee would be complete without the grateful acknowledgement of the help received from the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society. The large sums of money which it raises year by year for the evangelization of heathen women and children, has made possible the recent extension of our work in the way of boarding and industrial schools — a system of training which is already achieving an improvement in the morals, the manners and the intelligence of the children, such as never could have been expected by means of day schools, where the teaching during the day, however good, is too often neutralized by the blighting influences to which the pupil is subject morning and evening in a pagan home (A&P 1893, FMC report, p. xliv).

Ten years ago we had three day schools, and these were all the schools we had. Now, in addition to three day schools, we have eight industrial and boarding schools, in which latter class it can easily be seen that the moral and religious training are greatly superior, because the missionary has control of the child all the time, and does not send him back every afternoon to the uncivilized and often filthy and pagan surroundings of the reserve (A&P 1895, FMC report, p. xviii).

Some students at Cecilia Jeffrey attempted to run away in response to the homesickness, abuse, and colonial attitudes fostered at the school. Students who ran away often did not make it home, or were quickly returned to Cecilia Jeffrey where severe punishment was used to discourage future departures. In 1967, an article written in Maclean’s magazine entitled “The Lonely Death of Charlie [Chanie] Wenjack” sparked national conversation by addressing the horrors of the Residential School experience, and in 2016 Gord Downie produced “The Secret Path”, an artistic project based on Chanie Wenjack’s story.

The body of Charlie Wenjack, a 12 year old Ojibway from the Marten Falls First Nation, Northern Ontario and student at Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School, Kenora, Ontario was found on Oct. 23, 1966 by railway tracks near Redditt, Ontario some 40 miles from the school. Wenjack was trying to walk home. (Bush, 2014, p.4).

[Chanie] had left Cecilia Jeffrey Residence bound for his home community, Ogoki Post on the Martin Falls Reserve and ‘collapsed and died of hunger’ beside the railroad tracks he thought would lead him home. When found ‘he was lying on his back… [wearing only] his thin cotton clothing… obviously soaked.’ He had no identification; he was carrying a glass jar with a screw top. Inside a half dozen wooden matches” (Milloy, 1999, p.286-287).

Students like Chanie used the resources they had at their disposal to process, and perhaps act against, the Residential School system. While the actions of students can today be labelled as resistance, it is impossible to understand the motivations of all students who attempted to escape, or protest, the Residential School experience. Despite the opacity of the children’s motivations, they were not the only parties of who took action against the Residential School system. The families and communities of students at Cecilia Jeffrey were vocal and active in advocating for the appropriate care for their children. The contract established between the First Nations of Shoal Lake, and The Presbyterian Church in Canada was a crucial part of this advocacy.

The contract between Shoal Lake Ojibwa and Presbyterian missionaries was an extraordinary document, consider the motives that drove the European champions of Residential Schools… The actions of the Objibwa at Shoal Lake suggested that they knew nothing – or too much – of the ends for which government and missionaries had developed Residential Schools in the latter decades of the nineteenth century in Canada (Miller, 1996, p. 120).

However, the Shoal Lake First Nations advocacy was not limited to this contract. Throughout the history of Cecilia Jeffrey School, the involved Indigenous communities held The Presbyterian Church in Canada accountable for the care of its students. Miller writes that the Indigenous communities surrounding Shoal Lake:

became quite expert in petitioning the Presbyterian officials about aspects of boarding-school administration to which they objected. In 1902 the leading men objected to the administration of the matron, who they perceived to be too strict, with the result that the woman tendered her resignation. She particularly objected to the fact that a contract between the Indians and her church limited what the missionaries could do and required that the children be ‘well-treated’. A few years later, the local Indian leadership had to protest again, this time against the removal of the missionary who had tried to enforce their wishes in the operation of the school. Chief Red Sky threatened that if the Presbyterians removed this man, ‘I will ask the Indian Agent to send the children to another school for we won’t have them here at all.’ This threat proved unavailing, and the Indian parents found themselves petitioning against excessive corporal punishment the next year (Miller, 1996, p. 347).

Additionally, the Indigenous Communities of Shoal Lake were active in monitoring the quality of education being received by students at Cecilia Jeffrey, and engaged in protest when needed.

As educational institutions, the Residential Schools were failures, and regularly judged as such. In 1923….[R.B. Heron, a Presbyterian minister and a former Residential School principal] said that parents generally were anxious to have their children educated, but they complained that their children ‘are not kept regularly in the class-room; that they are kept out at work that produces revenue for the School; that when they return to the Reserves they have not enough education to enable them to transact ordinary business – scarcely enough to enable them to write a legible letter.’ The school’s success rate did not improve. From 1940-41 to 1959-60, 41.3% of each year’s Residential School Grade One enrollment was not promoted to Grade Two. Just over half of those who were in Grade Two would get to Grade Six (TRC Summary, 2015, 71).

Reports from the Women’s Missionary Society (WMS) demonstrate that in addition to their advocacy work, the parents and home communities of the students at Cecilia Jeffrey would keep their children at home, or removed them from the school, if needed.

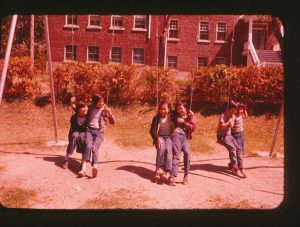

While much of the Residential School experience is characterized by sub-standard student care and evidence of underlying cultural genocide, students and staff at the Cecilia Jeffrey school also reported moments of lightness and leisure. These moments took different forms for each student, but often involved sports, arts, and recreation. In 1925, the Cecilia Jeffrey school was gifted a radio which provided entertainment for both students and staff (Missionary Messenger, March 1925, p.73). Some of the school’s staff also facilitated field-trips and outings. In the “Missionary Messenger”, one of the school’s instructors writes:

One afternoon, which I could not forget, was when Miss Houston and I and my little boys decided to have our supper at the water’s edge. Such a supper as we had and such fun preparing it. This is the menu: French fried potatoes, fried partridge, sardines, Johnny cake, bread and jelly, tea and candy. When we returned to the school we had a concert of gramophone music after which the happy little chaps went singing to their dormitories (Missionary Messenger, December 1923, 349-350).

Organized sports, particularly hockey, held a great deal of significance for some students in the Residential School system. This importance has been documented in news reports, memoirs, and in works of historical fiction, as well as in reports from the Women’s Missionary Society (WMS):

A good rink was flooded, and six hockey teams were organized. The boys like hockey best of all sports, and there is little trouble with discipline when they have this outlet for their excess energy (Annual Report 1943, p. 59).

The children are urged to participate in sports of all kinds. The school hockey team won the championship for the Kenora district and played in Winnipeg against the Winnipeg and Manitoba champion teams (Annual Report 1947, p. 57).

Since the termination of the Residential School system in Canada, and the 1994 Confession, The Presbyterian Church in Canada has worked with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada to facilitate healing for Residential School Survivors, and to foster more equitable relationships between itself and Indigenous communities. This process has led to a number of initiatives within The Presbyterian Church in Canada, with an aim to meet the recommendations listed by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, as well as the mandate of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. These initiatives include the church’s involvement in KAIROS, and the pioneering of a Healing and Reconciliation Seed Fund. As written the Confession of The Presbyterian Church in Canada:

We ask, also, for forgiveness from Aboriginal peoples. What we have heard we acknowledge. It is our hope that those whom we have wronged with a hurt too deep for telling will accept what we have to say. With God’s guidance our Church will seek opportunities to walk with Aboriginal peoples to find healing and wholeness together as God’s people (Confession, 1994).