The Mustard Seed began with Lillian Dickson’s generosity and compassion as she attempted to make the lives of those around her better, despite the lack of financial means or security that would eventually find its way to her. Today, The Mustard Seed organization has grown into that of an international organization with several national branches, including the Taiwan organization, which is now self-sufficient and has its own missions to other countries. The name, Mustard Seed, comes from a Bible verse, Matthew 17:20: “For truly I tell you, if you have faith in the size of a mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there’, and it will move; and nothing will be impossible for you.”

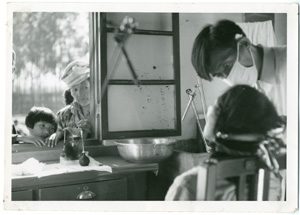

Throughout her lifetime Lillian would lead the way by providing better living conditions for those at the leprosy hospital; a medical infrastructure for those under The Mustard Seed umbrella, including those living in the mountains; homes for orphans and arranging adoptions – babies, children, and youths; opportunities through their academic school, trade school, babysitting school, agriculture school; and opportunities to young unwed women and couples to give birth to children in their maternity and women’s wards in order to escape social sigma and hardship. After her husband’s death, Lillian began to expand the reaches of The Mustard Seed in earnest to other nearby countries and islands, primarily in the form of schools, as a tribute to her husband.

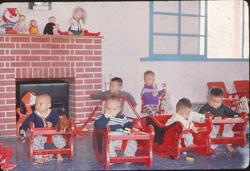

In the early days of Lillian’s work, which would become known as The Mustard Seed, the focus was primarily on patients at the leprosy hospital and their children. Health issues would arise if the children stayed with their parents from birth, but if separated shortly after birth they would generally grow up healthy. In 1951, Lillian describes the efforts and intent to create the infrastructure that could care for twin boys that were born from one leprosy patient’s wife:

We took the twins to the Mission Compound, begged for a tiny, temporary room for them, bought what they needed, got someone capable to take care of them, and then desperately thought of the next step. Nobody wants a leper’s child in their home. We borrowed money and bought a piece of land and a little house to put on the land. It was a prefabricated American little house which American aid to Taiwan had made as a model and suddenly put on sale. Now the house is being put on the land, the twins are gaining weight, and I am still negotiating with the Mission to Lepers to see if they are interested in saving lepers’ babies. If they fail me, then I must try elsewhere. ‘What would Jesus do?’ about the lepers’ babies? I believe He would try to save them, so cannot do otherwise. This will be a place of refuge for the lepers’ children and we will have a missionary nurse in charge to give them good care and loving care.

(1997-5006-1-2; circular letter dated November 23, 1951)

Within a year, Lillian notes in her circular letters to North America that more parents and babies are thankful for her efforts:

We have now ten babies born of parents with leprosy, six in our Home for Untainted Babies and four in the Observation home. Our family grows apace. One morning I went out to the Leprosy Colony to receive a wee child for the Observation Home. A group of lepers were waiting for me, and one […] stepped forward and presented me with a little package. ‘This is a gift of money towards the Church that is being built for us,’ he said. ‘here [sic] is also a gold ring someone wishes to give,’ The money has all been disinfected. We know it is not much, but we will still have more to give, and we want to do our part.’

[…] That night I entered the gift in my account book of the money so humbly disinfected and presented, and ‘one gold ring’ and remembering that so many of them have no fingers I wondered about the history of that ring.

(1997-5006-1-2; circular letter dated June 28, 1952)

Another passion of Lillian’s was caring for the young boys who were in the Children’s Prison for their petty crimes, such as stealing bread or clothing. She would often describe the horrible conditions of the prisons and how some would stay in prison after their term was finished, simply because there was no family to collect them and no home to return to upon release:

The children there are unbelieveably [sic] dirty, both bodies and clothes. There is a shortage of water, so they cannot wash thoroughly except once a week when they are taken some distance away to a stream. They drink trench water from the side of the road and that is used for cooking too. They are covered with scabies, and often beaten–. This little lad is an orphan. Once he stole something and thus was put in prison. His term is up, but he has no place to go. Another wee lad in prison is in the same position,- he stole two pieces of candy a year and three months ago. His term is up, but no one comes to take him out of prison.

(1997-5006-2-1; circular letter dated July 19, 1953)

Lillian resolved to find a place for them, and as such the Boys’ Home, at least in spirit until the physical home could be built, was created:

If we could build or rent a little home, not too far away [from the missionaries at the Leprosarium] as a home for four or five little boys, with a kindly motherly Formosan woman in charge, and the pastor nearby to see that they went to school, that might be a stop-gap until we get our Boys’ Home started. I call Sister Alma, the Lutheran nurse, the ‘angel in charge of the Colony’, and I asked her ‘Could you not let the boys be under the tip of your wing and give them some angel care too?’ We are praying to the Father to show us what to do.

(1997-5006-2-1; circular letter dated July 19, 1953)

By 1955, Lillian’s ‘The Mustard Seed, Inc.’ was officially registered and under her care was the government Leprosarium of eight hundred patients, the home for children of lepers, the Boys’ Home, the bamboo clinic and mountain clinic, as well as some orphanage work. One of Lillian’s most successful campaigns in the early years of The Mustard Seed was her request for used Christmas cards from North America: in her circular letters she would frequently ask that people send her the used Christmas cards for The Mustard Seed to stamp on their back page with scriptures and explanations of Christmas in Chinese. The cards were then handed out to anyone that The Mustard Seed sought to help within their care and on missionary trips into the mountains.

As time passed, the results of her efforts grew larger and yet, demand on the organization somehow continued to always exceed what Lillian and her organization could meet. Lillian sometimes expressed that she felt overwhelmed and wondered how she could possibly help all who sought her aid:

‘I can’t do it!’ one day I whispered to myself while at Po-li my eyes blinded with tears, The demands of the Po-li Christian clinics and the T.B. Sanatorium seemed stupendous, and we were overflowing on every side with patients. It was as if we were inundated with aborigines. We should have more land, more cottages, more workers, more everything.

‘Who can’t do it?’ A Voice questioned me in response to my whisper, and I was stunned by sudden self revelation. Did I presume to think ‘I’ had been doing this work? I have no money, no cleverness to plan,-from beginning to end it has been all of the Lord,-His plan, His support, His workers.

The acknowledgubg [sic] humbly that so far it has been all the Lord’s work, would I dare say ‘The Lord can’t do it!!’

(1997-5006-2-1; circular letter dated April 20, 1957)

However, Lillian was often reminded by her patients and their families of just how much her work meant to them. In fact, nineteen years after the twin boys were taken in by Lillian, their grandmother came to the Church of the Lepers to thank her:

My mind raced back to about twenty years ago when twin boys had been born at the Leprosarium, and I had taken them to my own home, for then we had no place for them. They were almost the first babies I had, and we soon established An-Lok, a Children’s Home for the children of the patients. Now the twins are extraordinarily handsome young men working in a factory. How the waves of history come back to wash against our shores! ‘I didn’t think they had a chance, but look at them now,’ went on the little grandmother immersed in her gratitude.

(1997-5006-2-3; circular letter dated January 30, 1970)

The Mustard Seed also sought to help children and their mothers and fathers prior to the child’s birth – the Taiwanese held identity certificates that could bear information leading to social sigma and therefore inability to gain employment or attend school without undue hardship:

In our Home for pre-wed mothers we are facing a peculiar problem. In this land if you have an illegitimate child, even if it is not your fault because you have been raped or some such thing, still it is solemnly inscribed into your residential certificate to be there for your life time. It is a slight variation of ‘The Scarlet Letter’ by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Nothing is done to the man,-he escapes all blame forever. So the girls try to dodge the issue by abandoning their baby, or selling it, or giving it away. The girls are usually so young, often still in their teens, and you feel so sorry for them.

(1997-5006-2-3; circular letter dated April 30, 1970)

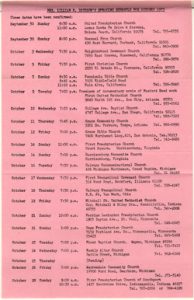

Lillian’s tour dates in the United States and Canada in 1973 (Items from file 1997-5006-2-3 at the PCC Archives)

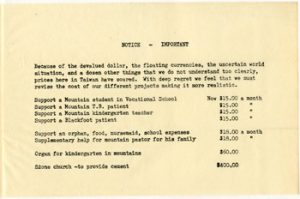

Helping so many people did not come easily or cheaply – Lillian received considerable assistance and support along the way through her donors, but particularly with the financial and personal support of Dr. Bob Pierce of World Vision. Lillian’s circular letters, pamphlets, and her yearly speaking tours helped people become aware of The Mustard Seed and its need for donations. Over time donations grew and at one point Lillian mused at the possibility of one day having a million dollars in order to accomplish much more:

‘When I have a million dollars, I will do many things,’ I said half to myself thinking of plans not yet accomplished. ‘You have had your million, and –you’ve spent it,’ a voice behind me said. It was Catherine, who is our office manager and assistant treasurer. ‘Spent it? For what?’ Of course she meant over the many years of working. My mind reeled a little as I reviewed what we had spent it for, and I did not regret any of it, for it was all for ‘meeting the needs of people and brining them to know the Lord.’

(1997-5006-2-3; letter dated April 30, 1970)

Only seven years later Lillian would write to her daughter, Marilyn, and reported bringing in over a million dollars in that year alone: “All the work goes very well,-we just have a hard time keeping up. We took in $1,160,000 [USD] this year,-perhaps I told you.” (1997-5006-3-3; letter to Marilyn dated August 15, 1977) In 2011 U.S. currency this would approximate $4,342,589.54!

Around 1975, Marilyn started helping Lillian with the writing of the circular letters while Lillian was on tour. Eventually Marilyn would complete the tours in North America and took over the letter writing completely – shortly after, in 1983, Lillian passed away in Taiwan.

This Project has been made possible [in part] by the Government of Canada through the Young Canada Works and Heritage Organizations Program. « Ce projet a été rendu possible [en partie] grâce au gouvernement du Canada par de Jeunesse Canada au travail et le Programme des organismes patrimoniaux». This exhibit was created by the Archives summer intern, Victoria Baranow.

*Copyright 2012 – The Presbyterian Church in Canada

If you wish to quote or use any part of this website exhibit, please give credit to The Presbyterian Church in Canada Archives.